|

Teaching with Teachers in Ethiopia

The doorways to the government school classrooms appear to be nothing more than intermittent black rectangles on a train-size stretch of turquoise walls. However, they are in fact, nothing less than gateways to a future of either failed or fulfilled possibilities. Inside, classes had just begun for a portion of the 2,800 students attending Alemu Woldehanna Primary School #3, a rural Ethiopian school in Hosanna, six hours south of Addis Ababa. The rest of the students attend successive sessions or shifts, the last of which extends into the hours after dark when Hosanna’s menacing hyena population emerge from their dens in search of anything they can catch from springhares to hapless humans. In the continuing movement towards realizing universal education, two or three school sessions a day has become common place for the approximately 20 million school – age children in the second poorest country in the world.

The doorways to the government school classrooms appear to be nothing more than intermittent black rectangles on a train-size stretch of turquoise walls. However, they are in fact, nothing less than gateways to a future of either failed or fulfilled possibilities. Inside, classes had just begun for a portion of the 2,800 students attending Alemu Woldehanna Primary School #3, a rural Ethiopian school in Hosanna, six hours south of Addis Ababa. The rest of the students attend successive sessions or shifts, the last of which extends into the hours after dark when Hosanna’s menacing hyena population emerge from their dens in search of anything they can catch from springhares to hapless humans. In the continuing movement towards realizing universal education, two or three school sessions a day has become common place for the approximately 20 million school – age children in the second poorest country in the world.

The principal of Alemu Woldehanna School gave me a welcoming smile and an invitation to visit the classrooms in his school. His reception relieved me of my newcomer’s jitters that I may have botched the greeting ritual with my utterance of Salemnu accompanied by a slight bow of the head and a grasp of the right forearm extended toward me. In the 3 days I had spent in Ethiopia I was still in the process of sorting out the salutations, handshakes, 2 cheek kisses and shoulder presses. These were not part of the preparation I had done for the early grade reading workshops and teacher- training activities I was scheduled to do during my one month stay. Those were to begin in 3 days but first I found myself accompanying my American friend, Helen Boxwill, to Hosanna. She has been living in Addis and working at the Ministry of Education but Hosanna is where she first conceived of creating a spacious library and community center, formed the NGO called h2Empower, and then, over the next 6 years, over- saw the arduous task of getting the library built.

The principal of Alemu Woldehanna School gave me a welcoming smile and an invitation to visit the classrooms in his school. His reception relieved me of my newcomer’s jitters that I may have botched the greeting ritual with my utterance of Salemnu accompanied by a slight bow of the head and a grasp of the right forearm extended toward me. In the 3 days I had spent in Ethiopia I was still in the process of sorting out the salutations, handshakes, 2 cheek kisses and shoulder presses. These were not part of the preparation I had done for the early grade reading workshops and teacher- training activities I was scheduled to do during my one month stay. Those were to begin in 3 days but first I found myself accompanying my American friend, Helen Boxwill, to Hosanna. She has been living in Addis and working at the Ministry of Education but Hosanna is where she first conceived of creating a spacious library and community center, formed the NGO called h2Empower, and then, over the next 6 years, over- saw the arduous task of getting the library built.

I was going to need a translator in order to interact with teachers and students on my self-guided school tour. Even though the children start to learn English in primary school their chances of becoming proficient are slim. They are first expected to learn to read and write in both the country’s working language, Amharic, and their mother tongue. However, since only a dozen out of eighty-seven different languages are selected for instruction across the country, the mother tongue a child is expected to learn may or may not be the language he or she hears at home. Placing those expectations in the context of a dearth of printed instructional materials (in any language); a traditional system of rote teaching and memorization; teachers whose spoken and written English challenge comprehension; and classes with as many as 95 students, it is not surprising that Ethiopia’s literacy rate hovers around 43% and only a fraction of public school students can pass the secondary school entrance exam which is given in English. My friend enlists an Amharic/English speaking acquaintance to accompany me on my self- conducted school tour. He is an intense fellow, who I learn early on, either does not quite grasp the concept of translating or refuses to be confined by it.

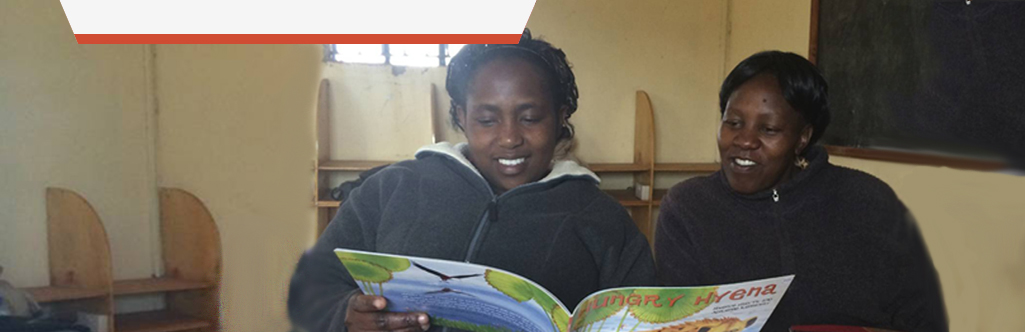

I quickly select a read-aloud picture book filled with fanciful animals doing silly things, from the library’s wide collection gathered from the donations of Long Islanders. I don’t really have a plan which feels strange for someone who had no intention of being an accidental tourist. But, looking back, I let the intentions that brought me to Ethiopia’s schools serve as my navigation system. I was aware of the nation-wide problems that had prevented the great strides taken to increase access to education for girls and boys, from increasing the quality of education as well. But I wanted to develop an understanding of what was possible at the classroom level and I guess more importantly, if I could use that understanding to play a role, somehow, in the work that had to be done. Would being in classrooms, reacting to students and interacting with teachers teach me which practices translate well and fit the Ethiopian context? Does it make sense to adopt expedient “remedies” like scripted, formulaic lessons aimed at boosting word recognition on national assessments? Or could the next step be showing teachers how to cultivate empowered and dynamic learners who would be prepared to share their talents and interests in their communities and in the workplace? It was with these questions and eager anticipation that I headed for the first open door.

Approaching the dimly lit classrooms from the sun-drenched field of weeds and sandy soil, it is impossible to get a preview of what is taking place inside. An element of surprise is inevitable for both the visitor and the visited. The students and teachers are tasked with processing the sudden appearance of a wide-eyed, blond lady, smiling broadly and awkwardly negotiating an unreasonably high step at the threshold of their room. Everything I had learned and read did not prepare me for the three-dimensional reality of rural schoolrooms in the developing world. A distant memory surfaced of my classrooms on a sweltering late June day, lights turned off in an effort to lower the temperature a degree or two. This also is a room slightly too dark for reading. Then there were the mud walls practically bare but for the peeling blue/green paint; wall- to-wall crude picnic style benches packed with youngsters attempting to share decrepit exercise books; a constant haze of dust amplified by a singular source of light entering through a narrow filmy window; and a lone, rough, loosely mounted slate board.

As soon as I am inside a sea of children are on their feet, “Good morning! How are you?” they sing out in perfect unison. I am surprised and delighted by their full-throated greeting. I smile and answer, “Good morning. I am fine. It is very nice to meet you. I am visiting from America. I am a teacher.” A ripple of excitement travels through the rows of well-behaved children and I introduce myself to their teacher who graciously accepts my intrusion into her class and her lesson. I ask, more with hand signals and facial expressions than words, if I may watch and perhaps participate in the teaching of English. She signals her invitation to stay in the front of the room and she continues to point to the English sentences on the board as she reads aloud, stops and points so the children can repeat what she has said. She does this 4 maybe 5 times for each word, each sentence. I ask her with the help of Teshome, my translator, “Do the children know what these words mean?” She smiles but does not say yes or no. I gesture toward the board, “May I? ‘ I take the nub of chalk in my hand and draw pictures to correspond to the

As soon as I am inside a sea of children are on their feet, “Good morning! How are you?” they sing out in perfect unison. I am surprised and delighted by their full-throated greeting. I smile and answer, “Good morning. I am fine. It is very nice to meet you. I am visiting from America. I am a teacher.” A ripple of excitement travels through the rows of well-behaved children and I introduce myself to their teacher who graciously accepts my intrusion into her class and her lesson. I ask, more with hand signals and facial expressions than words, if I may watch and perhaps participate in the teaching of English. She signals her invitation to stay in the front of the room and she continues to point to the English sentences on the board as she reads aloud, stops and points so the children can repeat what she has said. She does this 4 maybe 5 times for each word, each sentence. I ask her with the help of Teshome, my translator, “Do the children know what these words mean?” She smiles but does not say yes or no. I gesture toward the board, “May I? ‘ I take the nub of chalk in my hand and draw pictures to correspond to the  first sentence to illustrate pouring water in a kettle. I hope the teacher is as anxious as I am to find out if the children know what the words say and I wonder if she will continue to draw pictures once she sees that they do not. I know one of the reasons for the abysmal reading results (national assessments have shown that in areas like Hosanna, 54% of children couldn’t read one word at the end of third grade) and the 25% drop-out rate by second grade, is in no small measure due to the void of actual reading instruction in the primary grades. The concept of explicitly teaching reading beyond reciting the alphabet, words and sentences is as foreign as having cold weather apparel for your pet dog.

first sentence to illustrate pouring water in a kettle. I hope the teacher is as anxious as I am to find out if the children know what the words say and I wonder if she will continue to draw pictures once she sees that they do not. I know one of the reasons for the abysmal reading results (national assessments have shown that in areas like Hosanna, 54% of children couldn’t read one word at the end of third grade) and the 25% drop-out rate by second grade, is in no small measure due to the void of actual reading instruction in the primary grades. The concept of explicitly teaching reading beyond reciting the alphabet, words and sentences is as foreign as having cold weather apparel for your pet dog.

During this brief classroom visit and the others that follow that day, I discover and cling to my metaphoric connection with the folksy Johnny Appleseed. Perhaps this light casting of ideas and examples I am doing will take root and flourish. So I read aloud; act and draw words to life; ask the children questions that plumb their ideas and reactions; introduce thinking-pairing-and sharing; coach students through answering questions instead of turning to another student with a raised hand; and teach a phonics lesson or two. When I find myself in classrooms (two of them) without a teacher, I turn the customarily passive and quiet 4th graders accustomed to no-show teachers and having nothing to do in their absence, into an active and responsive picture book audience with or despite Teshome’s dubious translations.

I have one other unplanned visit while in Hosanna. A warm, energetic young volunteer worker named Melissa and a young idealistic private school principal, Belay Simeon, escort me from the library to a main thoroughfare a few hundred feet away. They hail the conveyance of choice in rural towns, a bajaje – a cross between a rickshaw and a 3 passenger rider-mower equipped with exceedingly ratty tarps, dilapidated seats, cracked plastic windshields, and blaring radio. We wend our way between bundle-laden donkeys and indifferent long-horned cows and over stonestrewn and rutted roads. Our destination -The Excellence Academy. It was the end of the school day when we arrived and the 110 students were outside as the three of us make our way to the school’s meeting room; a walk I would have called a “strenuous hike” if I were anywhere but Ethiopia. I made the newcomers mistake of whipping out my camcorder to capture the boisterous scene in the expansive school yard – so unlike ours with its innumerable and serious physical hazards. Who knew that all 110 youngsters would be up for getting their picture taken.

Meeting with the staff was a much more subdued encounter. The men, who were in the majority, were very soft-spoken and the women, as I was to find everywhere, were unwilling to speak up at all. Belay is unique; he is trying to create a culture of books and reading in his school. He wanted me to teach his teachers about teaching reading. While this is a goal shared by the Ethiopian government, and many U.S. and World Bank initiatives are underway, virtually nothing by way of teacher training has trickled down to the great majority of the country’s 320,000 primary teachers. This is a one-time opportunity for Belay’s teachers and I am very conscious of how little I know or understand about selecting the right combination of ideas (ideas they are ready to receive) and the right combination of words to communicate them. Melissa turns on my camcorder (I forget to tell her to open the lens cover) and I adjust my rate of speech as I begin to explain that teaching reading is like making doro wot – the ubiquitous spicy Ethiopian chicken stew served over the spongy pancake – injera.

Meeting with the staff was a much more subdued encounter. The men, who were in the majority, were very soft-spoken and the women, as I was to find everywhere, were unwilling to speak up at all. Belay is unique; he is trying to create a culture of books and reading in his school. He wanted me to teach his teachers about teaching reading. While this is a goal shared by the Ethiopian government, and many U.S. and World Bank initiatives are underway, virtually nothing by way of teacher training has trickled down to the great majority of the country’s 320,000 primary teachers. This is a one-time opportunity for Belay’s teachers and I am very conscious of how little I know or understand about selecting the right combination of ideas (ideas they are ready to receive) and the right combination of words to communicate them. Melissa turns on my camcorder (I forget to tell her to open the lens cover) and I adjust my rate of speech as I begin to explain that teaching reading is like making doro wot – the ubiquitous spicy Ethiopian chicken stew served over the spongy pancake – injera.

During our two and a half hours together I model how to teach some of the “ingredients” needed for reading with understanding; I hope I am answering the questions they ask and I suddenly feel a queasy mix of inadequacy, frustration, and sadness when a young man raises his hand, looks at me earnestly and says, “How are we to close the gap when we have never learned what we need to teach?” I struggle with finding an honest answer and I realize our time together has raised more questions then it has answered and perhaps, in the end, it has been a demoralizing experience for some.

Back in Addis, my experiences at the Mignon Lorraine Innis Ford School are complex, challenging, rich, and exhilarating. Knowing time is very short, I have a total of 5 days, I proposed a combination of a half-day teacher training workshop for the primary school teachers grades K through 3 to introduce the concept of teaching early grade reading; visits to one class on each of those grade levels; and coaching sessions with the teachers whose rooms I visited. The principal, a gentleman with regal bearing, is hungry for help for all of his teachers. He would like me to visit all 8 grades but we stick to the workable plan we arranged in earlier emails.

A schedule is improvised. I am advised not to drink water while working and to plan on a midday bathroom break at the Inter Continental hotel about a 5 minutes car ride away. It is advice I follow. I have the great good fortune to be accompanied by Jan, a thirty- something Ethiopian man who earned his MS from Columbia University in Computer Science. He will be translator, videographer, and driver as well. We begin the classroom visits on a Monday morning. During the first round of visits I observe the teachers’ English lessons for part of the time. Then I model ways to assess the children’s understanding of what is being taught and introduce new learner-centered practices. During the second round of visits I video the teachers applying the methods they observed. Our third meeting takes place in an area adjoining the principal’s office. I plan to show the videos and ask each teacher how she thinks her lesson went, did it accomplish what she wanted to and why, and what questions or comments did she have. I quickly find that asking for this level of articulation is not realistic even with a translator. So I break all the rules of cognitive coaching. I do most of the talking. I gush about the wonderful things they accomplished.

A schedule is improvised. I am advised not to drink water while working and to plan on a midday bathroom break at the Inter Continental hotel about a 5 minutes car ride away. It is advice I follow. I have the great good fortune to be accompanied by Jan, a thirty- something Ethiopian man who earned his MS from Columbia University in Computer Science. He will be translator, videographer, and driver as well. We begin the classroom visits on a Monday morning. During the first round of visits I observe the teachers’ English lessons for part of the time. Then I model ways to assess the children’s understanding of what is being taught and introduce new learner-centered practices. During the second round of visits I video the teachers applying the methods they observed. Our third meeting takes place in an area adjoining the principal’s office. I plan to show the videos and ask each teacher how she thinks her lesson went, did it accomplish what she wanted to and why, and what questions or comments did she have. I quickly find that asking for this level of articulation is not realistic even with a translator. So I break all the rules of cognitive coaching. I do most of the talking. I gush about the wonderful things they accomplished.

With minimal support, none actually aside from the model lesson, these teachers, some with no more than a 10th grade education, not only applied what they had seen but showed initiative, ingenuity, and joy in the process. Kindergarten teachers and their assistants from the 2 classes we worked with, planned their lessons together. First they led the spirited, morning group sing-along (too precious for words). Then the teachers led the children in a think-pair-share of their ideas before recording sentences for their second experience with a Morning Message. The crude board had been meticulously prepared for the English lesson. They selected the “en” cluster from the list I had given them and listed 5 words on the left side of the board.They introduced the use of colored chalk to differentiate the initial consonant. A picture for each word was drawn on the right side of the board. They drastically cut down the time for call and repeat as they named the words. Then the teachers engaged their students in matching, underlining, filling in initial consonants after they were erased, reading the words in sentences, and answering comprehension questions!

The second grade teacher searched for and found a story in the genre of “Goldilocks and the Three Bears” , which I read to her class. For her lesson she did a shared reading of “Amina and the Wolf”. Her teaching came alive as she dramatized, drew and asked questions all along the way! I quietly cheered her on from the sidelines as she experimented with the new found practice of posing questions that were not in the exercise book. The third grade teacher was less adventurous then her colleagues but she wisely decided to try to replicate what she had observed. It was her first interactive lesson – checking for comprehension, offering clarification and recording new vocabulary on the board. During our conference she said she much preferred discussing the reading with her students to the assignments in the exercise book. She felt this was the way children are taught in a private school.

The second grade teacher searched for and found a story in the genre of “Goldilocks and the Three Bears” , which I read to her class. For her lesson she did a shared reading of “Amina and the Wolf”. Her teaching came alive as she dramatized, drew and asked questions all along the way! I quietly cheered her on from the sidelines as she experimented with the new found practice of posing questions that were not in the exercise book. The third grade teacher was less adventurous then her colleagues but she wisely decided to try to replicate what she had observed. It was her first interactive lesson – checking for comprehension, offering clarification and recording new vocabulary on the board. During our conference she said she much preferred discussing the reading with her students to the assignments in the exercise book. She felt this was the way children are taught in a private school.

I had arranged for everyone involved in our little training to go out for a traditional Ethiopian lunch on our last day. Principal, vice-principals, teachers, teachers’ assistants, Jan and I were all in a celebratory mood. We have our own space in the back of the small restaurant. Our language barriers seem to duck out of the way as we laugh at our one-word jokes and respond to each other’s smiles and light touches. After eating I am presented with a lovely store- bought thank you card adorned with bright red roses and I am not the least bit surprised by the tightness in my throat and the moistness in my eyes as I hand out the Ethiopian equivalent of in-service credit – the highly prized yellow certificates each bearing an official purple stamp.

After note~

Using email to continue what we started is more challenging than I had first imagined while I was in the planning stage. The teachers I met do not have computer skills at all. The sharing of ideas continues with the young principals I worked with but they do not have computers of their own. Internet cafes are it for now and of course they are not free. Neither is printing. Wi-Fi access is spotty and where it is available it is unreliable.