In my last three blogs The “X” Factors, Saturday Meeting and Wander What We Must. I wrote about my thoughts and experiences at the start of the unique teacher education project I began last August in Maasailand, Kenya. Those blogs only hinted at the complex challenges and rich outcomes that would be the duel theme of the next six weeks and beyond. There’s much to tell and in the posts to come you will have a front row seat as the next unpredictable act unfolds.

Picture this. You are five or six years old. You live in a rural part of Kenya or Pakistan or India. Choose one. Your mother tells you today is the day you are going to start school. As she gives you the shirt, sweater and skirt that your older sister wore when she started school, she tells you, “You will have a teacher. You will learn. School is very, very important.”

You walk out into the chilly morning air with your mother and follow her as she deftly makes her way around the slippery craters created by last night’s down pour. Once at the road, your Mother points and tells you, “This is the way to go. Follow the road until you see the big house I showed you.” You do as you are told. If you are frightened you do not show it. Your pace is slow but you are serious about reaching your destination and eventually the unfamiliar shoes binding your feet carry you 8 rough kilometers (4.9 miles) to the place called “school”.

Your long, throat-parching walk had been exceedingly solitary save for the grazing goats, plodding cows and the occasional motor scooter that, most days, will blanket you in a thick cloud of dust as it zooms by. However, when you arrive at the tall iron school gate you are dazzled by the sea of children on the other side, more children then you have ever seen. Waves of them are flowing towards doors with teachers stationed outside. Swept up, you land in a bare room with walls the color of milk. The teacher starts speaking in words, many of which, you have not heard before. You take in all the clues you can. The others are squeezing their bottoms into the rows of benches. You squish in too.

The teacher makes white marks on the blackish wall. She points at them, speaks, points again, no one knows what to do. The teacher speaks again, points again, you can tell from her face she is waiting for the children to repeat what she says. They finally do. You and the others follow her lead and do this many times. You don’t know it but your teacher wants you to learn the names of colors although they are not the names you have heard at home and there are no colors in sight.

As I write, the vivid image of a precious little five-year old girl is still as fresh in my mind as if it were one of the mornings, 5 months ago, when my car driver stopped his Toyota in the midst of our jaw-jarring ride to Kimuka Village Primary School in Maasailand, Kenya. On the days that our coordinates converged, the sweater-clad, runny-nosed Kindergartener, making her way to the same destination, looked to see if she recognizes the man behind the wheel and then with a hint of hesitancy climbs into the back seat to sit along side the Mzungu (Kswahili for “white-skinned person”).

The little girl’s daily task of walking to and from school alone, looking like a speck against a vast and rugged landscape, was and still is, incomprehensible to me – the walk is extremely strenuous and rife with serious hazards. She is so unprotected! I thought of my own children at that age hopping on their school bus. Then another more profoundly disturbing thought followed. I was working with the teachers in her school. I had visited her classroom everyday and I knew that the hopes of the mother and the obedience and effort of the child were invested in a young woman with an eighth-grade education, equipped to provide little more than good intentions.

The education that hopes are pinned on in the developing world is the education that is leaving 2.5 million children, who do get to go to school, without being able to read a single word by the end of third grade. The causes for this failure are complex and numerous and not about to be solved anytime soon. Governments will not be distributing its funds equitably to all segments of society, tomorrow. Teachers in developing countries will not be paid a living wage, tomorrow. Books will not be available to all school children, least of all primary books written in the many mother-tongues, tomorrow. Infrastructures for connectivity will not be in place, tomorrow. But – teachers can be taught, tomorrow – if educators have the will to make that happen.

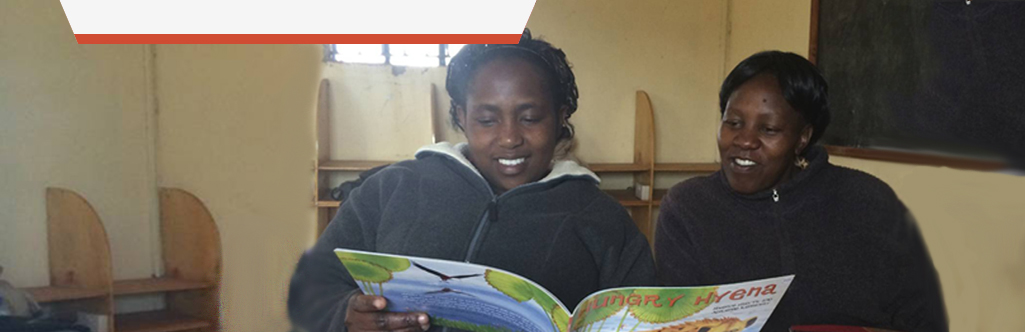

That is what my pilot project in Maasailand set out to test. Can providing primary teachers who have had very little training and working in a context of extreme scarcity, shift from traditional rote teaching to teaching that produces proficient and thoughtful readers and writers?

To be continued…